Vivian Maier is dead. And that’s our problem.

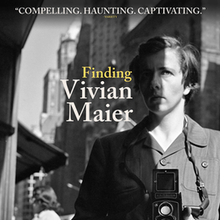

The sometimes gorgeous biopic, Finding Vivian Maier, brings the mysterious and secretive creative genius who chose to live out her life in obscurity back to life, and throws her unwittingly under the train. While stabbing wildly at her eccentricities, in the guise of celebrating her talent posthumously, the film takes Miss Maier exactly where she never wanted to go: to that merciless place where she would be forced to defend herself under the cruel stigmatizing microscope of a sensational mass media machine.

Maier lived her adult life as a nanny, dedicated to the children in her care, and as a curious ethnographer, dedicated to her love of cameras and their photographs, the art of street photography, and people. She lived when photography was expensive as an art, yet she did what she could to financially produce what she did; and, it was all for her personal pleasure, not for fame or recognition, which would have been hers, we all now know. But here’s her problem.

We live in a disposable world. Most people throw things out after use. Maier saved things after use, she saved what touched the moment, she collected the ephemera. Maier was a collector of life’s odd bits and pieces: junk, even trash, to anyone else, though precious to her life story. Genius does this. Winston Churchill saved his grocery receipts. In his 900-odd pages, abridged, Memoirs of the Second World War, we see why: it’s who he was. Collected receipts, even kitsch, can be valuable visual markers for brilliant, busy people. They can be time snapshots, revisited, mulled over again and again, research resources, rather than be seen as mere junk lost to the disposable archive. It’s how and why we cherish photographs. We need look no further than eBay to see how the disposable may hold personal, lasting value.

Why Maier never sought fame is intertwined with her obsession with news: her business and no one else’s. The film suggests, strongly, that Maier had a fascination with the macabre, the cruelties of mankind. It highlights salacious headlines from newspapers she saved, select texts, as possible evidence. Even though she saved piles and piles of newspapers with all kinds of texts — and images. And that is why Vivian Maier now has a problem, caught up in a form of legitimate, out of balance, socially justifiable muckraking. An example of what can happen should your vast volume of personal belongings somehow go to auction after your death and end up in the hands of a sincere yet naive buyer. They’re not buried with you, but are forced to stay alive, fed by a permanent life support system that you never approved.

Maier was all about the camera, the lens, the visual rhetoric. She reserved her interest in text for her audio cassettes. She didn’t save newspapers for their texts. She saved them for their images. Vivian Maier had a photojournalism bug and for reasons she took to the grave, never chose to pursue such a career. This film never suggests that motive, missing the forest for the trees, painting Maier as sinister, at times, with a secret ‘dark side.’ Well, we all do. That’s a major flaw in the film, not a balance, and an insult to the dead. Along with its presumption that a life worth living must naturally seek fame. The spectacle is incomplete without its endless sea of gawkers and grave robbers. Despite the prestigious gallery exhibitions of Maier’s photographs around the world, they remain hers, personally, and can never be rightfully ours. And alive, neither Maier nor her art could be bought.

Vivian Maier cannot be forgotten. Only grossly misunderstood in death as, undoubtedly, she was in life. This unsolicited film depicting select, novel elements of Maier’s deliberately private life, trying to piece her being together as a puzzle for now eight billion people to solve, must come up short. Yet that’s no reason why it should continue its mission; actually, it’s exploitation of a human subject unable to contest its relentless dissection of her being. No human being’s complex life can be fairly reduced to conjecture, let alone a damning, grasping for straws rooted in a finders, keepers careless mentality.

I have well over 100,000 personal photographs that I have taken over the years, reminders of where I was and when, some occupationally, some to share, others often a reflection of the moment for me to return to, at my leisure. Please don’t tell me that I must destroy them all before I die in order to keep them out of the hands of some grubby picker or curious thrifter who finds them, and is able to globally exploit them en masse for profit and visibility in a way that I may have never intended or pursued. They are mine, my memories, my moments; and if not bought from or given by me, never meant to be anyone else’s. As beautiful, haunting, and important the resurrection of the life and art of Vivian Maier in Finding Vivian Maier may seem to be, the matter cannot be denied its questionable place in the sacred realms of sanctity of human life, personal privacy, and dignity in death, all denied Vivian Maier in the end.

Vivian Maier is an excellent example why Europe acknowledges a Right To Be Forgotten. Were she able to speak from the grave, this remarkably talented, creative genius who lovingly cared for children not her own and who captured the momentous events of her camera’s rhetorical interactions with ordinary people on film day after day, might protest now being flaunted, profitably at that, on the world stage. Something which she never knowingly pursued or acknowledged wanting in this life. All while being permanently denied her basic human right to be forgotten, albeit in a digital age; seemingly, having lived her beautiful, dignified life ultimately as quietly, cautiously, and creatively as possible, with that sole intent.